Last weekend I went to Slutburn (yes, a pun on Saltburn), a queer-led, sex positive dance pop-up party in Chicago’s gayborhood.

A self-described “dance event celebrating human sexuality, self-expression, and absolutely unhinged summer indulgence,” Slutburn was a carnival of exposed skin, tantalizing (and usually skimpy) costumes, and sweaty dancing bodies. I wore a fishnet top and I was easily one of the most clothed people on the dancefloor.

Slutburn was indeed quite slutty—and unabashedly sex positive.

Given my research interests and the topics I usually write about, you may be wondering… what does this have to do with asexuality?

In short, Slutburn was a great example of something I’ve learned in my research: making a space sex positive and welcoming to asexual people are compatible goals.

Sex Positivity

Sex positivity and asexuality are sometimes perceived as existing in conflict with one another.

I think this is a mistake.

While I’ve argued in the Journal of Positive Sexuality that sex positive research and advocacy has a pattern of sidelining asexuality, I also see how asexual perspectives can strengthen sex positive frameworks.

Namely, asexuality calls attention to compulsory sexuality, or the sex-negative sociocultural imperative to pursue and engage in sex.

Sex positivity is all about combatting sexual shame. But it’s limiting to think that sexual shame is only related to the presence of sex and sexual desire. We can be—and asexual people often are—shamed for the absence of sexual activity and desire. Compulsory sexuality is sex negative because it shames us for sex we aren’t having or don’t want.

A focus on asexuality brings attention to compulsory sexuality, not because asexual people are the only ones affected by it but rather because asexual perspectives bring compulsory sexuality out of the shadows. Asexuality helps us notice compulsory sexuality and call it out as a sex-negative and shaming social force.

For this reason, I’ve argued that sex positivity and asexuality complement each other.

Consent is Slutty

Although I see sex positivity and asexuality as mutually supporting one another, there are certainly tensions between the two.

For example, in a recent publication in The Sociological Quarterly, I found that many asexual people had uncomfortable relationships with queer nightlife.

For some asexual respondents, this was simply because they had no interest in participating in sexually-charged spaces. Others, however, did want to be in those sexually-charged spaces. But they also wanted infrastructure for more clearly signaling consent (and non-consent) to physical touch.

In other words, most of the asexual people I interviewed didn’t want queer nightlife to be desexualized. They simply wanted more robust frameworks for opting out of the specifically sexual elements of queer nightlife.

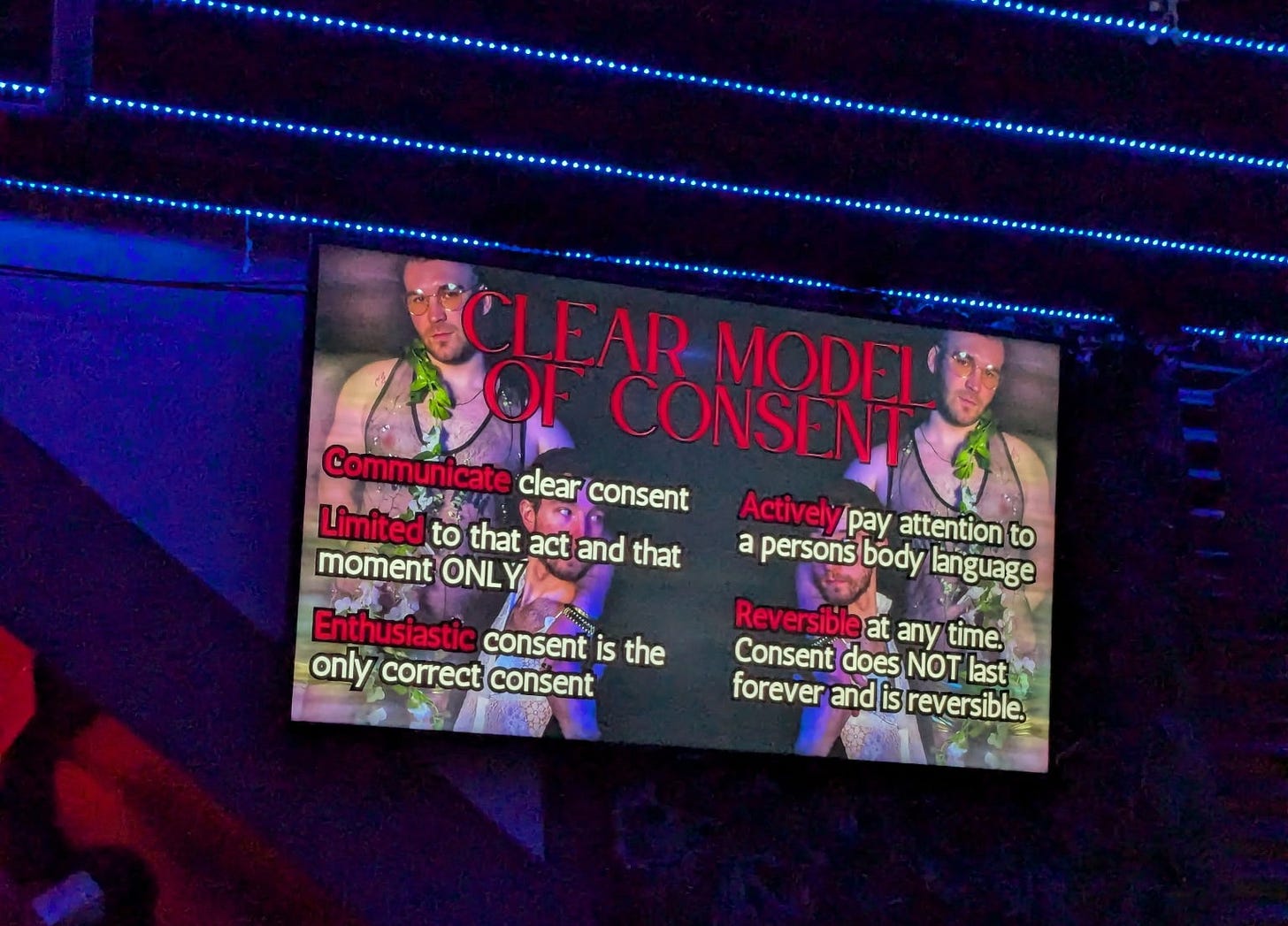

That desire to be able to easily opt out benefits even those who do want to participate in the sexual elements of queer nightlife. That’s because sex positivity is about expanding our freedom to participate in sex—but it is also about enabling us to decline intimacy that we don’t want. Consent is core to sex positivity.

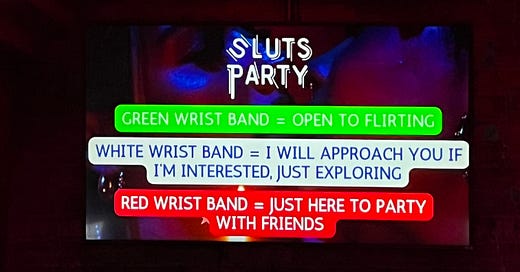

The organizers of Slutburn baked consent frameworks into their event. Attendees were asked to choose a colored wristband when they entered: green for “open to flirting,” white for “I will approach you if I’m interested,” and red for “just here to party with friends.”

It made it feel safer and more comfortable to be “slutty.”

Moreover, this wristband system directly echoes recommendations asexual interviewees gave when I asked them how to make queer nightlife better for asexual people.

For example, Jane, a young asexual woman from Arizona, explained:

I went to this party once in college, and they had this multi-colored cup system that you could use to show people whether you were open to making sexual connections or not. Like pink cups meant you were open to it, blue meant you weren’t, green meant maybe you were, or something like that. I thought that was such a smart idea . . . Even though it was party where a lot of people wanted to hook up, I didn’t feel weird being there . . . I could totally imagine even expanding that to have different colors show whether you were okay with being touched or not. Maybe even wristbands or something instead of cups.

When I saw that Slutburn was using almost exactly the system Jane described, I knew I needed to write about it.

After all, the issue of consent isn’t just a problem for asexual people. As I note in my Sociological Quarterly article, scholars have noted various traumatic experiences of non-consensual touch among non-asexual queer people in gay clubs. Touching and consent are points of contention in nightlife, whether you’re asexual or not.

Slutburn shows that even explicitly slut-affirming and sex-positive events can benefit from the same strategies that will help asexuals.

Queer people, including those who are asexual, are uniquely positioned to (re)imagine consent and how to have ethical sexual interactions. Efforts to welcome asexual people can make sexualized spaces safer and more approachable even for individuals who wish to engage sexually with others.

Canton Winer is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Northern Illinois University. His research focuses on the relationships between gender and sexuality, with specific focus on the experiences and perspectives of people on the asexuality spectrum. You can keep up with his research on Bluesky.

Want to support my research on asexuality? Consider becoming a contributing subscriber by clicking on the button above. I am committed to keeping my work free, without paywalls. Consider your paid membership a token of appreciation, an investment in research on asexuality, and a small but meaningful way to join a community that shares your interests.

This is SO well said and I love how you connect Compulsory Sexuality to Sex Negativity! Sharing!