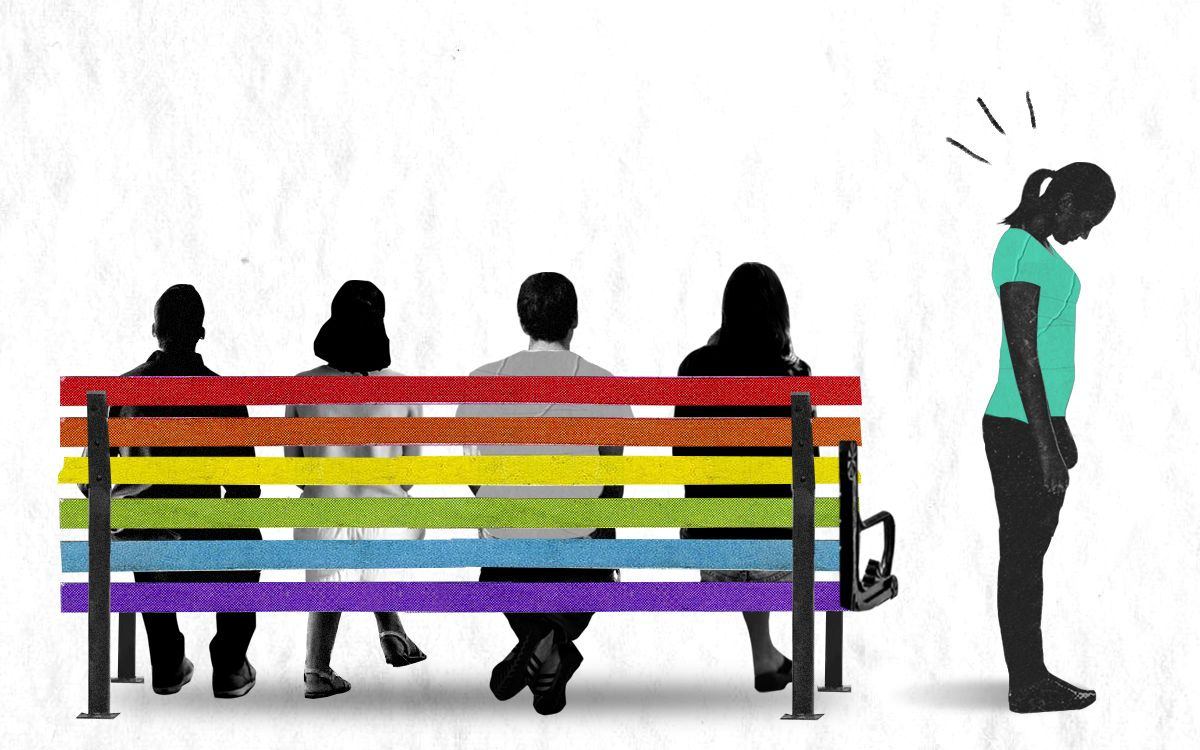

When Gini’s friend Brandon invited her to accompany him to Pride, Gini was thrilled. She had come out as asexual to Brandon earlier that year and had never been to Pride. “This is gonna be really fun and really cool,” Gini remembered thinking.

But the feeling quickly soured. “We get to Pride, and [Brandon] tells me that he’s never had an ally come to Pride with him before.” Gini’s excitement curdled into aggravation and disappointment. She wasn’t an “ally.” She was queer.

As I explain in a recently published article in Contexts, this story is not unusual for asexual people. Asexuality is often sidelined or even completely erased in queer spaces.

If you’ve been following my research for a while, you know that I’ve argued repeatedly that asexuality is queer. In the Contexts article, “Is Asexuality Queer?”, I expand those thoughts into a full length, peer-reviewed article.

The argument is simple: queerness is about opposition to normativity. Asexuality names and calls our attention to compulsory sexuality—that is, the assumption that all people are (and should be) sexual. In a society that assumes everyone does and should experience sexual attraction, it’s queer to say that you don’t.

Asexuality scholars and activists thus argue that asexuality reveals an unstated cultural ideal normalizing sex—a norm that exists in both queer and non-queer spaces.

That’s no small point. By identifying compulsory sexuality as part of the architecture of human relationships, asexuality offers a queer challenge to queerness itself.

Compulsory Sexuality

Queer research and activism often involve pulling back the curtain on cultural norms that are hidden in plain sight. By centering the experiences of queer people, scholars and activists have revealed how ideals like the gender binary and heteronormativity are subtly (and not so subtly) woven into our social fabric.

As a non-asexual (i.e. allosexual) queer person who studies asexuality, I’ve seen that asexuality reveals a number of norms that shape how we experience the world. By highlighting compulsory sexuality in particular, studying asexuality pushes us to examine sex as part of the normative architecture of society.

As I discuss in Contexts, compulsory sexuality shows up all over our social world. In modern Western culture, sex is typically seen as a necessary component of healthy romantic relationships. Sexless romantic relationships are often treated as problematic, unnatural, unfulfilling, wrong.

Compulsory sexuality even emerges in the law. Under section 12 of the United Kingdom’s Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, for example, a refusal or inability to “consummate” could be grounds for annulling a marriage in England and Wales. In her 2016 article “Divorcing Marriage from Sex,” legal scholar Sally Goldfarb notes that U.S. marriage law has also traditionally required that married couples perform (heterosexual) genital intercourse.

Compulsory sexuality also shows up in medicine. Research on conversion therapy1 (or attempts to change a person’s sexual/gender identity, expression, or orientation) suggests that asexual people are also likelier than any other LGBTQIA+ identity to be offered or have undergone conversion therapy. Conversion therapy aside, asexual individuals often have experiences of doctors treating their sexuality as a medical problem.

Compulsory sexuality can even feed into interpersonal violence. Disturbingly, multiple asexual people have told me they’ve been offered (read: threatened with) corrective rape when others learned they were asexual.

This isn’t an exhaustive list of the ways compulsory sexuality emerges. But hopefully this gives an idea of how far-reaching this cultural norm is.

Asexuality’s queerness stems from its relationship with compulsory sexuality. In fact, I see asexuality’s identification of compulsory sexuality as an important contribution to queer politics. As I discuss in Contexts, I think this is far from asexuality’s only contribution (with the split attraction model being another obvious example).

Queerness as a Resource

Studying asexuality has led me to think of queerness as a resource. In my view, asexuality adds richness and nuance to queerness that expand that resource.

For example, the openness of asexuality to adopting multiple sexual identity labels at once is an exciting complement to the growing recognition of sexual fluidity. Ideas like the split attraction model could be useful beyond asexual communities, providing a helpful framework for thinking through the complexities of sexuality, romance, and identity.

Similarly, although compulsory sexuality is particularly harmful for asexual people, we can also consider how these pressures can negatively affect those who do not identify as asexual. Queer movements have often focused on combatting shame for the desires we do experience, but perhaps there is additional value in addressing shame for the desires we do not experience.

These are merely glimpses into the possibilities asexuality opens up for queerness. As awareness of asexuality rises, its potential contributions to queerness will likely multiply.

Asexuality is part of a broader queer shift that has unfolded rapidly in the past two decades. We are witnessing the emergence of new terms that help people express and make sense of themselves, connect with others, and mobilize for social change. Some of these terms may feel strange at first—queer, if you will—even to queer people. Yet acknowledging the variety and complexity inherent to the ever-growing queer umbrella broadens the scope of queer politics by revealing hidden (and not so hidden) social norms, like compulsory sexuality, that structure how we live our lives.

Liberation is not a limited resource. We expand its power by acknowledging that sexual normativity comes in various packaging. Next time Gini goes to Pride, I hope she finds fellow queers ready to embrace the queerness of asexuality.

Canton Winer is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Northern Illinois University. His research focuses on the relationships between gender and sexuality, with specific focus on the experiences and perspectives of people on the asexuality spectrum. You can keep up with his research on Bluesky.

Want to support my research on asexuality? Consider becoming a contributing subscriber by clicking on the button above. I am committed to keeping my work free, without paywalls. Consider your paid membership a token of appreciation, an investment in research on asexuality, and a small but meaningful way to join a community that shares your interests.

Conversion therapy is pseudo-medical at best, but it is also not limited to medical settings. Some conservative religious groups also push these harmful practices.

It's wonderful to read your keen insights into topics related to asexuality. Your argument that queerness is best defined as the opposite of heteronormativity resolves a lot of the issues around who gets to claim that label -- and who doesn't. I'm also glad you're addressing violence, abuse and trauma faced by ace people in a world that defines everything in terms of sex. Even if they haven't experienced those things, many aces have had painful experiences in relationships.

I'm always cautious about terms that group disparate things together (relevant here, "LGBTQIA+" and "queer") because they have a tendency to treat one person's priorities as co-extensive with another's. Hence, I tend to see the 'queer community' as a loose confederation rather than a homogeneous whole. By way of example, the interests of trans-people and lesbians can overlap in some circumstances (e.g. discrimination) and clash in others (e.g. single-sex [I use the word advisedly] spaces). Hence, even though it's exasperating, debates over who is 'queer' may be inevitable. I tend to assume people at least have goodwill even if they say something irksome.

Looking at the big picture, however, I think we will have to work together on a political level as time goes by. Looking at political discourse, I think semi-compulsory natalism will emerge as the driving idea in the West over the next decade (especially if the world is saddled with President Vance). For obvious reasons, this may prove particularly oppressive to the non-heterosexual population. Feuding over who is 'queer enough may' become a luxury nobody can afford.